In the early summer in London, Leighton House Museum will hold an exhibition of the works of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, entitled “Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity,”( from 7th of July,); and also this year, the British Museum will hold an exhibition of artworks by a Japanese artist, Hokusai Katsushika, entitled “Hokusai Beyond the Great Wave,” (from 25th of May). The juxtaposition of Alma-Tadema’s exhibition at Leighton House with the Japanese art show at the British Museum may sound irrelevant, but the pair can bring us a new thought in considering the contexts of nineteenth century art history.

There were two different enthusiasms for the artists in the later Victorian period: One was Japanese art; and the other, antique art. J.M Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and French impressionist painters, for example, showed great interest in Japanese art, especially Japanese wood-block prints, traditional costumes and interior decorations. On the other hand, Frederic Leighton and Laurence Alma-Tadema were fascinated with antiquity, exploring the modern rendering of imaginative life in the ancient Greek and Roman periods. Bearing the seemingly unrelated contexts of the Victorian Japonism and revival of antiquity in mind, I would like to consider the work of Lawrence Alma-Tadema in this post.

Were the nineteenth century Japonism and classicism linked ? A Victorian art critic and promoter of Greek art and culture, Walter Pater, makes a comparison between Greek sculpture and Japanese print in the following way.

The ideal aim of Greek sculpture, as of all other art, is to deal, indeed, with the deepest elements of man’s nature and destiny, to command and express these, but to deal with them in a manner, and with a kind of expression, as clear and graceful and simple, if it may be, as that of the Japanese flower painter. (Walter Pater, Greek Studies, London: Macmillan, pp.230-1)

Pater observes that the expressions of clarity and simplicity in Greek sculpture and Japanese art/print are something they have in common: Both groups of artefacts convey the artists’ unmediated aesthetic sensibilities and expressions, being the sheer embodiments of human nature. Also perhaps their arts connoted some “primitive”, “innocent” or “savage” aspects, since they had been produced, for the Victorian viewers, in an uncivilised period (Greco-Roman time) and the uncivilised far East (Japan). The Victorians’ admiration for those exotic and simple works may be associated with their skeptical and anxious reaction to the reality of the rapid modernisation, imperialism, urbanisation, and industrialisation undergoing at the time.

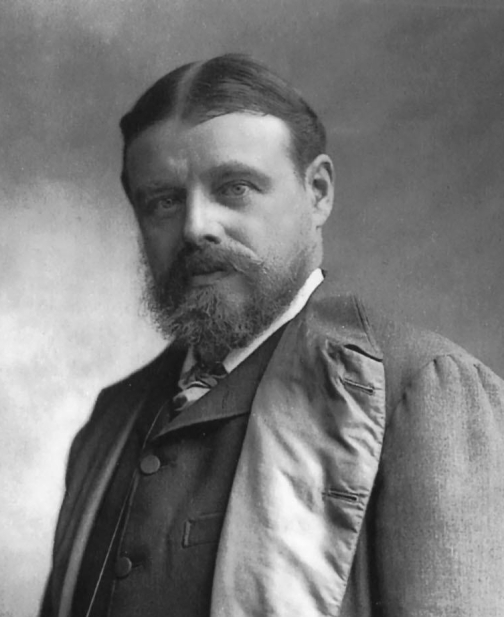

Lawrence Alma-Tadema — born in Dronrijp, the Netherlands, and trained at Antwerp, Belgium— settled down in London in 1870. The subject of his paintings was predominantly classic, especially Roman, and significantly contributed to the classical movement in the late Victorian period. However, his classicism does not necessarily echo Victorian escapism but implies contemporary life. Elizabeth Prettejohn points out the parallel elements in Alama-Tadema’s Roman images and the Victorian life, in terms of urbanisation, imperialism, and corrupted morality. Thus Alma-Tadema reveals some contemporary elements through the depictions of the classical worlds.

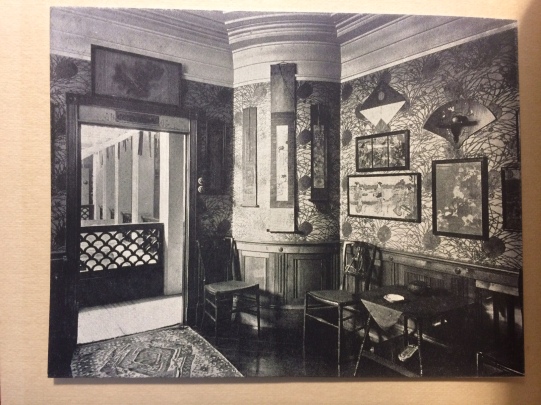

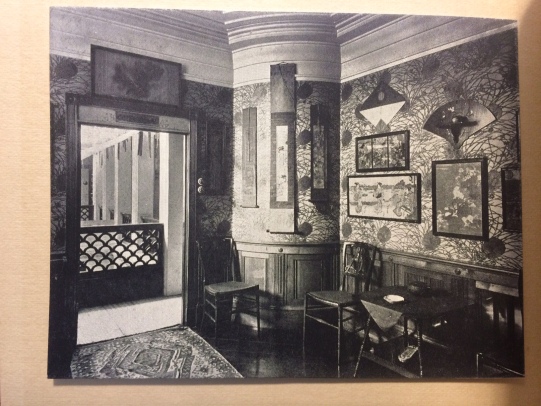

Whilst Victorian classicism seems a major theme in discussing Alma-Tadema’s work, I would like to view his work from a different perspective, that is, as you expect, an element of Japonism. In fact, Alma-Tadema was an avid collector of oriental artefacts. His flamboyant studio house at 17 Grove End Road, St. John Wood was decorated with his eclectic art collection including Roman, Egyptian, Chinese, and Japanese objects. In one of his dressing rooms, Japanese prints and “kakemono” (hanging pictures) were displayed. In 1892, Alama-Tadema joined as a charter member of the Japan society that was founded in order to promote Japanese art and culture, and became the Vice President in 1895. It is clear that he was very enthusiastic about Japanese art. However, scholar R.J Barrow suggests that there was no direct influence of Japanese art on his work because he only enjoyed it as hobby. Yet it can be said that he had a keen and experienced eye for Japanese art as the Vice President of the Japanese society.

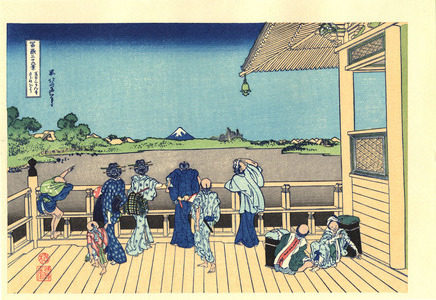

What makes Alma-Tadema’s paintings modern is his arrangement of unconventional compositions, which, I think, resembles to the compositional arrangements of traditional Japanese prints. The aspect of Japanese wood-block prints that shocked the western artists was the ways in which the Japanese artisans had undermined the rendering of three-dimensional space in their pictures. In the nineteenth century, to create the three-dimensional spaces was imperative as a tradition of western painting. The Japanese prints, by contrast, adopted birds-eyes views, leaving unnatural blank spaces (as I have explained in my older post on Mary Cassatt) with unusual compositional arrangements.

Let us see some examples of Japanese prints depicting waterside scenes. One of the popular compositions for woodblock prints is that human figures view a famous landscape from the balcony. In Hiroshige Utagawa’s Views during the Four Seasons at Famous Places in Edo: Moon Light at Takanawa (Edo Meisho Shiki no Nagame), three female figures, relaxing on the balcony, are depicted at the foreground. The figures almost block the landscape behind. But they also play a role in inviting the actual viewer to join them to observe the landscape together. The landscape behind, mainly the sky, sea and moon, is simply described. Its simple rendering makes the elegance of women’s attire stand out, thus the beautiful female figures also become objects to view for us. It has been pointed out that a series of Japanese waterside prints influenced French Impressionist paintings that depict urban leisure time at waterside, including Édouard Manet’s Boating (1874), Argenteuil (1874), Claud Monet’s The Beach At Trouville (1870) and The Blue Row Boat (1887) to name but a few.

The composition of which female figures at the foreground with the views of an empty waterside in the background can frequently be seen in Alma-Tadema’s paintings too. The Kiss (1891), Her Eyes are with her Thoughts and They are Far Away (1897), Silver Favourites (1903), and A Coign of Vantage (1895) are cases in point. In them, the relaxing female figures make a contrast to the vast empty views behind. The horizontal lines, the symmetrical and geometrical lines of the balustrades make an aesthetic relation to the unstrained female figures.

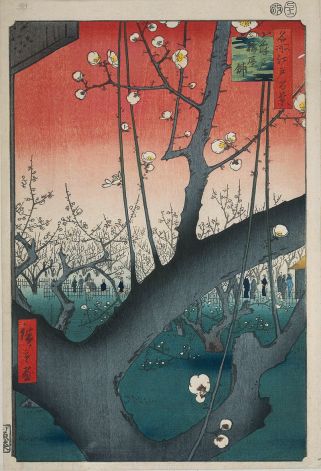

The Baths of Caracalla (1899) shows an unconventional composition too: The three female figures become predominant at the foreground and a big column blocks a tantalising view, naked bathers, behind. This compositional arrangement was famously used in Hiroshige’s Plum Park in Kameido: As in Alma-Tadema’s The Baths of Caracalla, the composition of this picture shows that one of the plum trees is predominantly displayed at the foreground and one can vaguely see some people at the background.

Alma-Tadema thus consciously employs a new “perspective” in the representations of antiquity. I believe that his unconventional and unique arrangements of composition were drastically further developed by twentieth century modernists who questioned and deconstructed the perspectives traditionally employed in the western paintings.

If you have a chance to go to both exhibitions, Alma-Tadema’s and Hokusai’s, you could try imagining and making an analysis of the connections between the art of Japanese prints and that of Alma-Tadema’s classicism.

[References]

Elizabeth Prettejohn, ‘Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the modern City of Ancient Rome’ in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 84, No. 1 (Mar., 2002), pp. 115-129

R J Barrow, Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Phaidon: New York, 2011)

Leave a comment